Robert Ashley

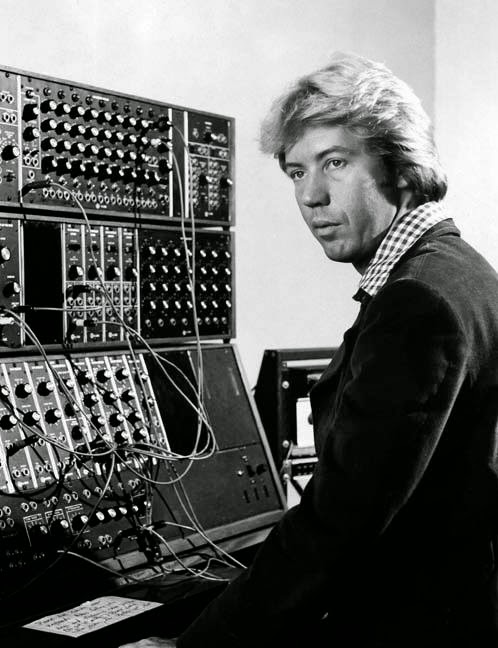

(March 28, 1930 – March 3, 2014) was an American composer, who was best known for his operas and other theatrical works, many of which incorporate electronics and extended techniques.

Ashley was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He studied at the University of Michigan with Ross Lee Finney, at the Manhattan School of Music, and was later a musician in the US Army. After moving back to Michigan, Ashley worked at the University of Michigan's Speech Research Laboratories. Although he was not officially a student in the acoustic research program there, he was offered the chance to obtain a doctorate, but turned it down to pursue his music. From 1961 to 1969, he organised the ONCE Festival in Ann Arbor with Roger Reynolds, Gordon Mumma, and other local composers and artists. He was a co-founder of the ONCE Group, as well as a member of the Sonic Arts Union, which also included David Behrman, Alvin Lucier, and Gordon Mumma. In 1969 he became director of the San Francisco Tape Music Center. In the 1970s he directed the Mills College Center for Contemporary Music.

"Automatic Writing" is a piece that took five years to complete and was released by Lovely Music Ltd. in 1979. Ashley used his own involuntary speech that results from his mild form of Tourette's Syndrome as one of the voices in the music. This was obviously considered a very different way of composing and producing music. Ashley stated that he wondered since Tourette's Syndrome had to do with "sound-making and because the manifestation of the syndrome seemed so much like a primitive form of composing whether the syndrome was connected in some way to his obvious tendencies as a composer".

Ashley was intrigued by his involuntary speech, and the idea of composing music that was unconscious. Seeing that the speech that resulted from having Tourette's could not be controlled, it was a different aspect from producing music that is deliberate and conscious, and music that is performed is considered "doubly deliberate" according to Ashley. Although there seemed to be a connection between the involuntary speech, and music, the connection was different due to it being unconscious versus conscious.

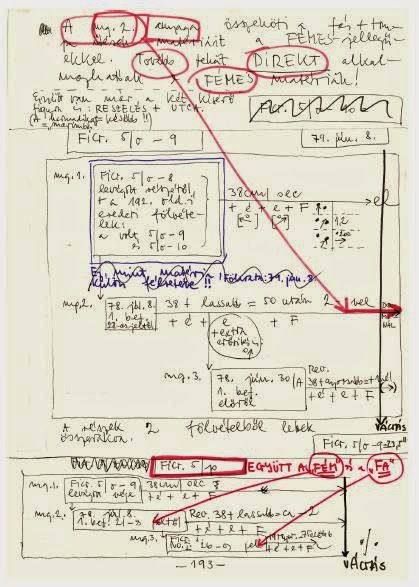

Ashley's first attempts at recording his involuntary speech were not successful, because he found that he ended up performing the speech instead of it being natural and unconscious. "The performances were largely imitations of involuntary speech with only a few moments here and there of loss control". However, he was later able to set up a recording studio at Mills College one summer when the campus was mostly deserted, and record 48 minutes of involuntary speech. This was the first of four "characters" that Ashley had envisioned of telling a story in what he viewed as an opera. The other three characters were a French voice translation of the speech, Moog synthesizer articulations, and background organ harmonies. "The piece was Ashley's first extended attempt to find a new form of musical storytelling using the English language. It was opera in the Robert Ashley way".

In the dialogue for Automatic Writing, the words themselves were not necessarily the primary source of meaning—especially not after the kind of audio manipulation Ashley used to modify them. Some of the dialogue became totally incomprehensible.[1] Ashley appreciated the use of voice and words for more than their explicit denotation, believing their rhythm and inflection could convey meaning without being able to understand the actual phonemes.

Ashley engineered the first version of the piece using live electronics and reactive computer circuitry. He recorded his vocal part himself, with the mic barely an inch from his mouth and the recording level just shy of feedback. He then added "subtle and eerie modulations" to the recording, modifying his voice to the point that much of what he read could not be understood.

The piece included four vocal parts that changed over the life of the piece, but in the final recording, the pieces included Ashley's monologue, a synthesized version, a French translation of the monologue, and a part produced by a Polymoog synthesizer.(Wiki)

Robert Ashley: Automatic writing (1979)